All investing is a relative, not an absolute, game. If the stock market pops by 25 percent in one year and your fund is up 18 percent, you’re sort of a loser. If your fund gains 2 percent and the market loses 20 percent, then you’re a rock star. This same type of relativity applies to investment options—stocks, bonds, commodities, and even, perhaps especially, commercial real estate and REIT shares. Capital always seeks the highest relative return, and that bodes well for continued foreign investment in U.S. real estate.

This theory of relativity means that, based on yields, U.S. commercial real estate is a bargain, a shocking statement to many investors. Going-in cap rates today are similar to, and in many cases lower than, 2007-era pricing; however, global investors approach the math differently than do U.S. domestic-only players.

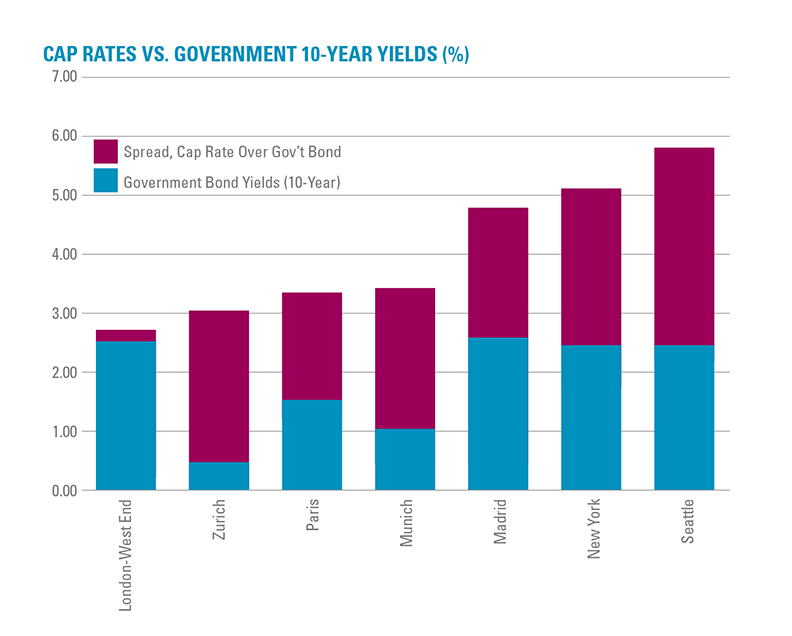

First, global investors look at nominal yields in comparable markets. As shown in the table below, cap rates of approximately 5.1 percent for average institutional-quality office buildings in New York are low, but compared with rates for prime assets in London’s West End (2.7 percent) or Zurich (3 percent), New York yields look positively juicy. Likewise, for investors willing to venture further afield to Madrid, which has an average cap rate of 4.8 percent, Seattle (5.8 percent) is a pretty fair deal. Are there super-prime buildings in the U.S. markets that trade for lower cap rates than those shown? Sure, but that doesn’t change the moral of this story: The U.S. markets boast a good relative current yield against similar assets in the old country.

Second, investors weigh risk premia—what is the spread between the government bond rate in each country versus the office assets one can buy there? In other words, how much does the investor get paid for taking all the risks associated with owning an office building, versus buying the “risk-free” local government bond?

In this case, investors get a scant 0.2 percent premium for buying a prime London office building versus 10-Year British government gilts, and that is a very skinny premium indeed. The next skinniest risk premium is for Paris, where prime offices are a 180-basis-point premium over French government 10-year bonds. Madrid is a little richer with a 2.2 percent spread over Spanish government 10-year bonds, which is about in line with New York’s 2.6 percent spread. Seattle sports a wide spread at more than 300 basis points over the 10-year Treasury.

In this case, investors get a scant 0.2 percent premium for buying a prime London office building versus 10-Year British government gilts, and that is a very skinny premium indeed. The next skinniest risk premium is for Paris, where prime offices are a 180-basis-point premium over French government 10-year bonds. Madrid is a little richer with a 2.2 percent spread over Spanish government 10-year bonds, which is about in line with New York’s 2.6 percent spread. Seattle sports a wide spread at more than 300 basis points over the 10-year Treasury.

So, U.S. real estate risk premia not only appear very attractive, but on closer inspection, may be even better than they look. Are the political and other risks associated with prime assets in Madrid equivalent to average institutional assets in New York or Seattle? Personally, I’d take the apple pie and hot dogs over the paella.

Sure, it’s conceivable that all real estate worldwide could be overpriced, and in the event of a global recession, commercial real estate values would likely fall hard. However, from a global investor’s viewpoint, the U.S. is looking very good.